REACHING THE FINISH LINE

Gods, mother-tongues, poetry, and the bravery of truthful expression.

Ala Ghawas, accomplished Bahraini singersongwriter, tells all about his latest album and his newfound sense of peace.

The artist, who put out his first Arabiclanguage album late last year with the eminent Bahraini composer and musician Isa Najem after eight consecutive English-language releases, feels that he finally found a way to express himself with a complete sense of honesty and vulnerability.

When asked about his refrain from the language with his previous eight albums, he says: “If you asked me this question 10 years ago, I don’t think I would have had an answer for you. But right now, me turning 40 and moving on with my life, I think that answer is very, very clear. I think what made me run away to the English language is because English gave me that free zone to express myself without me being necessarily questioned by people in my society.

“I don’t write about the simple romantic stuff. My songs are very daring, they can be very bold, they can sometimes be offensive, because they touch on several aspects of life including religious, social, even intimate matters. If you don’t get personal, in any form of art, your art means nothing. People want to know what you’ve gone through.” Despite feeling proud of his earlier work, Ala says he always felt there was a ‘mask’: “No matter how hard I tried to be sincere, it took me time to be brave enough to openly discuss such poetry in Arabic and be proud of it.

Bob Dylan once said that if you want to examine your honesty and your openness by writing a song, you need to feel as if you were naked walking in the streets. With this one, I felt that. It’s scary expressing yourself in Arabic. I never managed to get to the finish line with my earlier albums. But with this one, I feel like I did.”

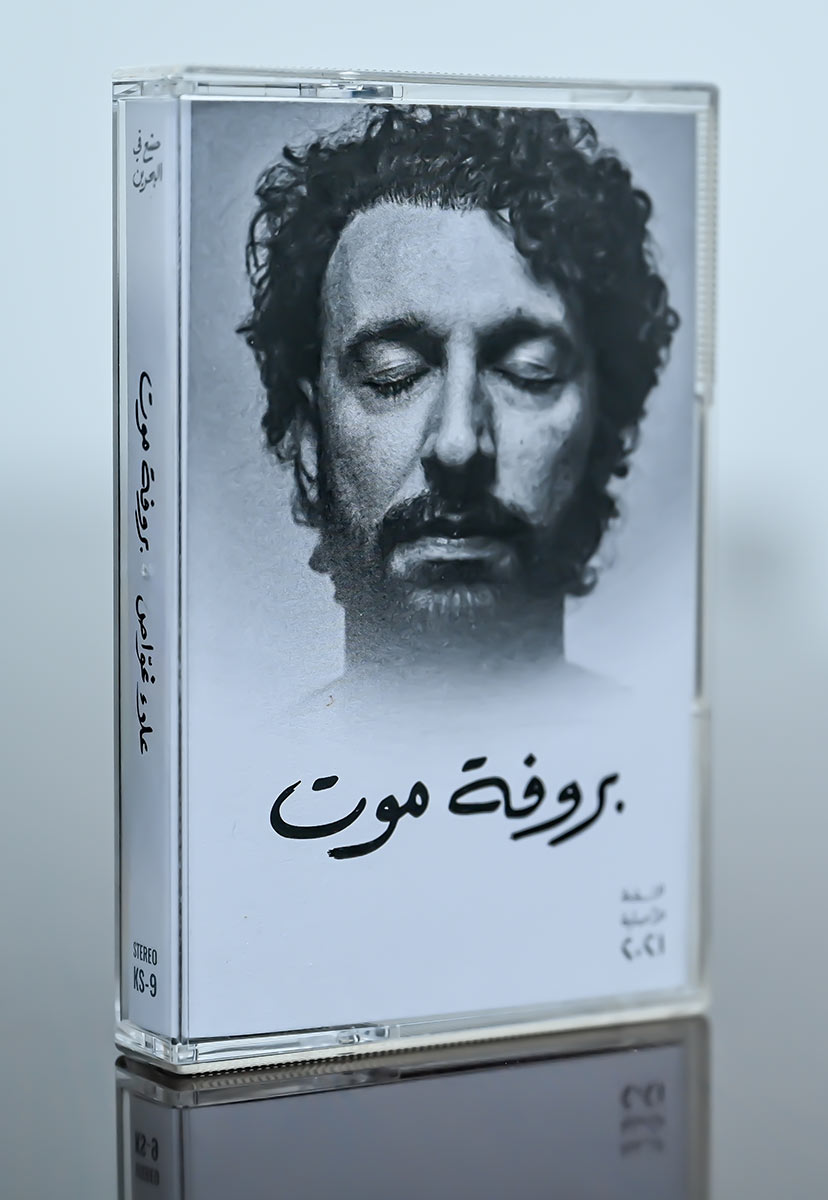

The album, Brouvat Mout, translating to ‘Death Rehearsal’ (‘Brouvat’ being inherited from the Italian ‘Prova’ meaning ‘rehearsal’) was prompted by the passing of his grandmother as well as a close family friend, respected novelist and screenwriter Fareed Ramadan, in 2020.

“It just made me reflect on the whole idea of losing someone for good. When you have your grandparents around, you feel you’re still young and so far away from death. But when they go, you look behind you and suddenly you only see your parents, no one else.”

Singing in classical Arabic for the first seven tracks and in the colloquial Bahraini Arabic in the last, dubbed Mashmoom, Ala “flirts with the theme of death and its many faces”.

One of the songs, named Alihat Al Muharraq or ‘The Gods of Muharraq’, was inspired by the only three visits Ala ever made to the Muharraq cemetery, the first being in 2011 to bury Ali Bahar, a prominent Bahraini singer known as the ‘Bob Marley of the Gulf’, and the second and third being in 2020, to bury both Salman Zayman, also a famous singer, and ‘Uncle Fareed’—“three very influential figures in the art community in Bahrain; all from Muharraq and buried in Muharraq. I wrote the song as a tribute to them, the legends of Muharraq, and those that are still around as well.”

Another track, Khalf Quthban Al Jana translating to ‘Behind the Bars of Heaven’, is a satirical imagined future where Ala and his friends go to heaven and realise they prefer life. Additionally, Dam Al Ruman or ‘The Blood of Pomegranates’, is an invitation to his wife Fatema to ‘die with him,’ so as to say that life alone is not enough time to spend with her. The song that has hit the charts, however, is Mashmoom, named after the basil plant locals adorn graves with, and which in the past was used as a fragrant accessory at weddings, braided into the hair of the bride as well as showered on newlywed couples.

Not being a big fan of modern technology and digitalised music and having produced the album as an ode to his Bahraini roots, Ala chose to release the album as a cassette, wanting to revive the old-fashioned way of listening to music—much like he did as a child in the eighties and nineties—hoping that listeners will appreciate its nostalgic quality.

With his chin resting on weaved fingers, Ala recounts his earliest memory with music, playing the accordion at eight or nine years of age, encouraged by his music teacher, Mr. Maani Abdulaziz, who was the first to instil in him a love for the craft, and who Ala is still in touch with till this day. Being from a family that is quite artistic, with a poet for a mum and the renowned painter Abbas Al Mosawi for an uncle, his creative talent was continuously nurtured.

Unbeknownst to most, Ala thinks of himself more as a poet sometimes, with a strong belief in the power of words and the cathartic gusto of literary flair. “If you don’t have that good sense of poetry, your music becomes very thin. If you’re a good guitar player, but you don’t read, you can jam but you can never write a song. I don’t think I would ever have released a single record if I had no poetry coming out of me.”

Speaking of the written word, Ala hopes to release a book next discussing his experience with identity and the questions he has grappled and struggled with.

He expresses his gratitude towards his parents for giving him the freedom to flourish as he wanted, to his wife for always being by his side, and to his friends for their encouragement, especially Isa Najem, who he thinks of as “the most gifted musician I’ve ever met and who could steer the music scene in Bahrain for the coming decades.” ✤

Comments are closed.